Topic 3.2b Ocean Resources

Topic Aims

In this topic we will consider

- how fish and shellfish are harvested

- if we can harvest more fish

- how overfishing and habitat degradation are affecting fish harvests

- Aquaculture, and

- a case study of the Southern Bluefin Tuna

Ocean Resources

Oceans contain almost all of the earth's water (97% water is saline in oceans and salt lakes) and cover nearly 71% of the earth's surface.

Our current understanding of many aspects of ocean ecology is still relatively poor. As a result caution in our use of marine resources is essential. In order to manage these resources carefully co-ordinated action between nations is required as oceans are common property and even near coastal waters and the resources they provide are subject to influences from other nations. As common property oceans tend to suffer from the phenomena known as "tragedy of the commons". Since the oceans belong to everybody they should be everyone's responsibility. However, everyone's responsibility tends to be nobody's responsibility without some form of ownership to direct control of maximum fish yields and ensure sustainable resource use.

There is a range of environmental and resource use issues concerning our oceans, however, in this topic we will be specifically focusing on ocean fisheries and the ecosystem goods these populations provide. Globally marine fish production is the worlds largest source of either wild or domestic animal protein, particularly in tropical developing countries. However, this constitutes a small part of our global calorie consumption(<1%; Lomborg 2001).

There are several issues facing the fishing industry:

- Sustainability of fish harvest

- Ecological impacts of harvesting

- Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing

- The role of aquaculture

These issues all revolve around the one central theme of maintaining the ecosystem services that produce harvestable fish and using fish farming to augment these natural processes.

![]()

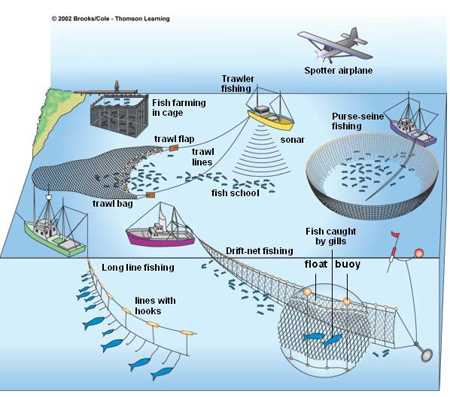

How are fish & shellfish harvested?

Ocean fisheries are the worlds third largest major food-producing system.

Fisheries are concentrations of particular aquatic species suitable for commercial harvesting in a given ocean area or inland body of water.

Activity 3.32

Read pages 257-260 Miller & Spoolman (2012) and describe the various fish harvesting methods discussed. Which are the most environmental sustainable method(s) and why?

![]()

Can we harvest more fish & shellfish?

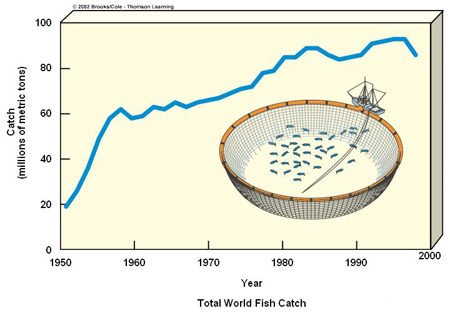

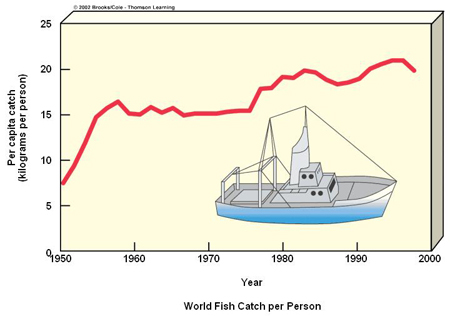

Between 1950 and 1982 the annual commercial fish catch increased almost five fold while the per capita seafood catch more than doubled.

However, the bad news is that despite all the additional effort and technology, the commercial fish catch has increased little since then and the per capita commercial fish catch has been falling since 1982.

Fish are renewable resources as long as the annual harvest leaves sufficient breeding stock and habitat for the species to reproduce and replenish numbers for the next years harvest. The major problem with utilizing fish as a renewable resource is determining the size of the fish catch that can be harvested without depleting the remaining breeding stock. There are many factors that contribute to this problem including; lack of scientific knowledge, species that are targeted by a number of different fishing industries, unregulated catches, and misreporting of catch sizes.

Annual Sustainable Yield = the size of the annual catch that could be harvested indefinitely without a decline in the population of a species

Overfishing = a harvest of fish that exceeds it’s sustainable yield, i.e. taking too many fish out of the breeding population so that the species declines over a number of years.

Commercial Extinction = when the population of a species declines to the point of no longer being profitable for commercial fishing.

Activity 3.33

Read Miller & Spoolman (2012), page 287-288, and answer the following:

- Describe the trend in global fish harvest since 1950.

- What percentages of the world’s major fisheries are being fished at or above their sustainable capacity?

- What is the good news Miller identifies?

Activity 3.34

Read Miller & Spoolman (2012), p 287, and discuss how government subsidies have contributed to over fishing.

![]()

Is Aquaculture the answer?

Aquaculture involves raising fish and shellfish for food and supplies about 33% of the worlds commercial fish harvest. Production in this industry increased fivefold from 1984 to 2001.

Activity 3.35

Read Miller & Spoolman (2012), pages 287 and 308-309 , and answer the following:

- Describe the two basic types of aquaculture

- With reference to Miller & Spoolman (2012), Figure 12-20, p296 and the accompanying text, construct a table comparing the advantages and disadvantages of aquaculture.

Advantages and disadvantages of aquaculture Advantages of aquaculture Disadvantages of aquaculture Your answers Your answers

- What are the new trends and research that may help decrease the harmful effects of aquaculture?

![]()

Case study: Southern Bluefin Tuna

The southern bluefin tuna (Thunnus maccoyii) is a valuable migratory species of fish that inhabits the open ocean. This species is can live up to 40 years and takes a long time to reach maturity. Breeding takes place in the warm waters south of Java Indonesia. Juveniles then migrate south down the west coast of Australia towards New Zealand and also west through the Indian Ocean towards South Africa. Thus the species travels huge distances across high seas and into the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of a number of countries, including Australia and New Zealand, which brings it into contact with fishing industries in a number of countries. These biological features of the fish along with its virtually life-long exposure to fishing pressure creates a fish population that is slow to recover from depletion relative to other shorter lived species, including most species of tuna.

As the southern bluefin tuna (SBT) breed in one location and all look alike wherever they are found they are managed as one breeding stock. However, to achieve unified management requires the co-operation of all countries whose waters the SBT enters and who fish the species. The species is fished commercially be Australia, New Zealand and Japan. Originally SBT was targeted for tuna canneries, now most of the fish caught are fattened in aquaculture pens and destined for the fresh tuna market in Japan. High levels of fishing between the 1950s and 1980s caused serious depletion of the adult stock, and studies suggest stock levels may be less than 10% of the 1960 level.

Formal management of SFT began in 1994 when Australia, Japan and New Zealand established the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT). The commission set annual national allocations between it’s establishment and 1996-97 when no agreement could be made on subsequent years quotas. Scientists and fisheries managers of the three countries had differing views on the capacity of the stock to withstand additional fishing and prospects for the recovery of the species under current fishing levels. An additional problem that plagues the conservation of the SBT is fishing by countries outside the CCSBT, which continues to increase. Efforts are being made to bring the fish catch of non-member countries under the management of the commission. Despite the problems faced by the CCSBT, this case study provides an example of the need for international co-operation to manage our ocean resources and some of the problems this involves.

![]()

Review questions

- Explain how fish can be used as a renewable resource and some of the problems of managing ocean fisheries in this way. Support your answer with references to the SBT case study.

- Describe trends in the world fish catch since 1950. Assess the potential for increasing the annual fish catch and use of aquaculture.

- Distinguish between fish farming and fish ranching. What are the pros and cons of aquaculture?

![]()