Rainforest diversity, disturbance and gap-phase dynamics

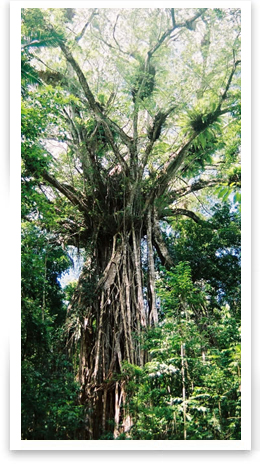

Given the dense nature of rainforest canopies, the creation of a gap in the canopy is a significant event in that resources, namely growing space and light, are made available to the competing tree species. Canopy gaps are usually created by a disturbance event such as treefalls of over-mature canopy trees, through to large, extensive canopy gaps created by storms, cyclones or fires. Gap creation (Figure 4) sets in train a complex process of rainforest succession and re-growth, often referred to as gap-phase dynamics (Osborne 2000).

Figure 4 Canopy gap formation, in this case Cyclone Larry 2006, which did extensive damage to the rainforests of Far North Queensland. Photo courtesy of Ian Dixon.

Canopy gaps have a complex physical micro-environment, with a range of 3-dimentional shapes, sizes and orientations. Over extensive rainforest blocks, disturbance processes and resultant gap creation results in a mosaic of canopy structures, with patches of forest at differing phases of recovery following disturbance and gap formation. This mosaic of patches contributes to the concept of structural diversity supporting biological diversity as gaps of differing sizes and ages (time since disturbance) provide a wide variety of microclimates and thus growth conditions within the forest environment. As a result, we see the evolution of particular plant and animal 'guilds' - groups of species who are able to exploit the unique conditions found within canopy gaps of different sizes and phases (ages) of rainforest succession.

As a gap ages, re-growth and colonisation by a range of plant species occurs usually starting with 'pioneer' species, fast growing shade intolerant species who invade the newly formed, high light gap environmental.

For an illustration of ecological and physiological properties of plant species adapted to a range of canopy gap conditions review Table 8.4 in the chapter by Osborne. A similar table could no doubt be constructed for animal species as well.

Eventually these pioneer species die out or are out-competed and the forest becomes dominated by late-phase or mature phase species. This is a simplification of the process, but in essence, the secondary or post-disturbance forest recovers via succession until the forest recovers and has a similar structure and range of plant and animal species of the pre-disturbance or primary forest. For complex rainforest types, this process may take a century or more.

Disturbance and diversity

How does disturbance relate to diversity ?

A prominent theory explaining the maintenance of high diversity in rainforests is the 'intermediate disturbance hypothesis' of Connell (1978). This suggests diversity is maintained in ecosystems that experience an intermediate level of disturbance. Ecosystems exposed to extreme levels of disturbance would support only highly adaptive species that could survive such an environment. Little or no disturbance would result in competitive exclusion processes excluding many species.

![]() Recall Activity 3.1 where we learnt that tropical regions

are relatively stable, with constant climatic conditions infrequent

storms or other disturbance events that generate single or multiple-

tree gaps, i.e. intermediate levels of disturbance. Such intermediate

levels of disturbance are thought to enhance diversity as these events 're-set' populations to low levels, reducing competitive exclusion and

a wide range of species are thus maintained over time.

Recall Activity 3.1 where we learnt that tropical regions

are relatively stable, with constant climatic conditions infrequent

storms or other disturbance events that generate single or multiple-

tree gaps, i.e. intermediate levels of disturbance. Such intermediate

levels of disturbance are thought to enhance diversity as these events 're-set' populations to low levels, reducing competitive exclusion and

a wide range of species are thus maintained over time.

What evidence is available to support this notion of high diversity maintained by disturbance regimes in tropical rainforests? What happens when the disturbance regime is changed e.g. by logging (large gap creation) or climate change induced shifts in storm frequency and / or intensity?

![]()

Activity 3.3

Diversity and disturbance

To answer some of these questions we need some more background on rainforest dynamics and disturbance.

Read the chapter entitled 'Forest Dynamics' from Whitmore T.C. (1998) “An introduction to tropical rain forests”.

This chapter examines rainforest microclimates of intact forest mosaics and canopy gaps and the growth properties and regeneration ecology of different gap specialists. This further develops the introduction to gaps dynamics provided by the Osborne (2000) reading.

Q1 What changes are there to forest microclimate when canopy gaps form ? Contrast the ecological and physiological properties of the so-called pioneer and climax species.

![]()

Disturbance to the canopy results in a large increase light quantity and a shift light quality (spectral properties) reaching the lower canopy layers and forest floor. Soil temperature is elevated, with an increased diurnal range. These environmental signals stimulate germination of pioneer or gap specialist tree species, thus setting in motion rainforest succession.

Pioneer tree species are light demanding and can not survive or reproduce beneath the intact canopy. These species have a large soil seed bank that is able to quickly change to altered microclimates. Within a gap environment, competition for light and growing space is high and these species are usually short-lived (10-30 years) with high photosynthetic and height growth rates. By contrast, climax species have no seed bank but can germinate in shade and are able persist beneath the canopy.

Large gap formation favours results in a significant alteration to the canopy microclimate and light-demanding pioneer species out-compete the slower growing climax species. However, the long-lived climax species eventually dominate gap species over time and reform the primary forest.

Gap size is a critical factor in determining the mix of species that colonise a gap. Small gaps may have periods of the day where the within canopy space is in deep shade and climax species will be more competitive than pioneers. Pioneer and climax species represent two ecological extremes - in reality there is a continuum of responses to gap creation, with differing species types dominating at different phases of the recovery process. This gives rise to a highly diverse mosaic of gaps in different phases of recovery, all intermingled with intact patches of primary (undisturbed) forest.

If a disturbance event is large (e.g. a cyclone), complex lowland rainforest may take up to 100 years to fully recover the diversity of species that existed prior to disturbance.

Q2 How is a knowledge of forest gap dynamics useful for silvicultural (timber production) operations and forest management in general?

![]()

Traditional rainforest silviculture involved the manipulation of gap sizes linked to a knowledge of regeneration requirements of commercial species to favour their growth. Seasonality of flowering, fruiting and seed rain must also be known to ensure seed is available during regeneration phases. If a harvest regime is to be sustainable, it needs to mimic the natural gap creation and disturbance regime of a forest and follow rules of minimal impact extraction. Post-harvest seeding may also be needed if seed trees are not available in close proximity to the site of extraction.

This is a highly contentious area of management - strict adherence to scientific principles reduces harvestable timber volumes per annum and is expensive to implement - in developing tropical countries often practices are poor or non-existent with forest degradation resulting. In Queensland, the scientific model used by forestry industries for rainforest logging was essentially rejected as being unsustainable. However, this is a debatable issue and we will discuss this issue further in Module 4.

![]()

Activity 3.4

Impacts of intense disturbance events - Hurricane Joan and regeneration processes of lowland rainforests of Costa Rica

Let us examine the impact of a large disturbance event (Hurricane Joan) on rainforest dynamics. Read the paper by Vandermeer et al. (2004) who tracked height growth and species dynamics over a 14 year period after Hurricane Joan of 1988 which caused extensive damage to a lowland Nicaraguan rainforest. This paper tracked re-growth and colonisation within canopy gaps damaged by the hurricane. The Introduction provides a good overview of theories associated with disturbance regimes and maintenance of high diversity in tropical rainforests. Table 1 of this paper provides a good example of classification of the regeneration niche that they occupy. Note that these authors used more than 2 types (pioneer and climax) - there is a range of classifications used to better capture the diversity of regeneration requirements of this diverse rainforest.

A 14 year study of recovery is a short period relative to the duration over which gap-phase regeneration will occur at this site. What trends in regeneration were evident after this relativity short period of recovery?

![]()

The hurricane devastated patches of the forest and created a large gap. Rapid height growth occurred in the years following the disturbance with intense competition for light resulting in tree mortality and thinning of the canopy. Even after a relatively short time, different species groups and cohorts are starting to dominate. Winners and losers and the development of a canopy structure is evident - larger individuals are forming an upper expanding canopy of pioneer species, while individuals below this layer are in slow decline. The development of an upper canopy by these pioneer species will in turn produce ideal conditions for later stage climax species to successfully regenerate.

Next topic -Australian rainforests - an overview

Topics in this module

- Introduction

- Fundamentals of rainforest ecology

- Rainforest diversity, disturbance and gap-phase dynamics

- Australian rainforests - an overview

- Threats to rainforest ecosystems

- Case studies - Fire management in the Amazon

- Compulsory readings